Before the revered architect IM Pei agreed to design Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art, he embarked on a quest to discover the essence of Islamic architecture

Words Andrew Humpreys

The Road to

Top Image: IM Pei at the opening of the Museum of Islamic Art in 2008. Photo: © Keiichi Tahara

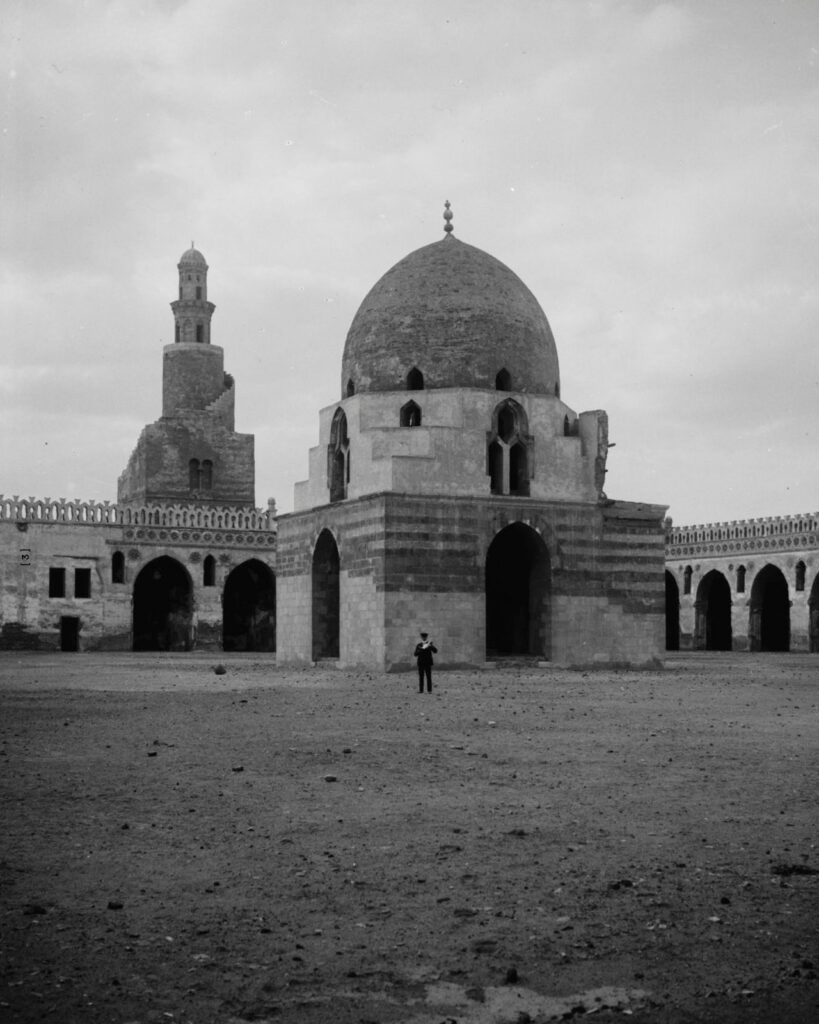

Ahmad Ibn Tulun was a former Turkic slave-soldier serving the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, who climbed the ranks and, in 868, was sent to govern Egypt. Once there he used the wealth raised by his taxes to expand Cairo, adding new quarters, palaces and pleasure gardens and – so legend has it – a pool filled with mercury on which he could loll on inflated cushions, manoeuvred by slaves with silken ropes. He endowed the city with a magnificent mosque, named after himself, and declared Egypt independent from the caliph in Baghdad.

Ibn Tulun died 16 years after taking up his post on the Nile, and the dynasty he founded lasted just one generation before the Abbasids regained control of Egypt in 905. But his legacy endures, largely thanks to his mosque, which was a direct inspiration for what global design magazine Dezeen calls one of the 25 finest buildings of the 21st century: Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art (MIA).

The Doha museum project began in 1997 with a competition organised, at the request of Qatar, by the Aga Khan Foundation. Eight international architects were invited to submit designs, including Zaha Hadid (UK), Hans Hollein (Austria), Arata Isozaki (Japan), Richard Rogers (UK), Oriol Bohigas (Spain), James Wines (USA) and the two who were eventually shortlisted by the jury: the Jordanian/Palestinian Rasem Badran and Charles Correa of India. A Qatari panel, which included then minister of culture and heritage Sheikh Saoud bin Mohammed Al Thani, settled on Badran as the ultimate winner.

Badran was given time to develop his preliminary concept, but the plans he subsequently presented were for a structure that, in the view of Luis Monréal, the chair of the competition jury, probably could not be built, at least not in the way the architect was proposing. With the competition failing to produce a successful outcome, it was suggested that the Amir of Qatar, His Highness Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, simply choose an architect of his liking. His choice was IM Pei – his striking Louvre Pyramid had been unveiled in 1989 and had obviously made an impression on the Qatari ruler.

Monréal knew Pei personally, and he accompanied Sheikh Saoud to meet the architect for lunch at his club in New York, where their proposal was politely but firmly turned down. Pei explained that he was old (he had just turned 80), had retired from full-time work and had built what he considered his final project, the Miho Museum in Japan. On top of that, he said, he was not an expert on Islamic architecture.

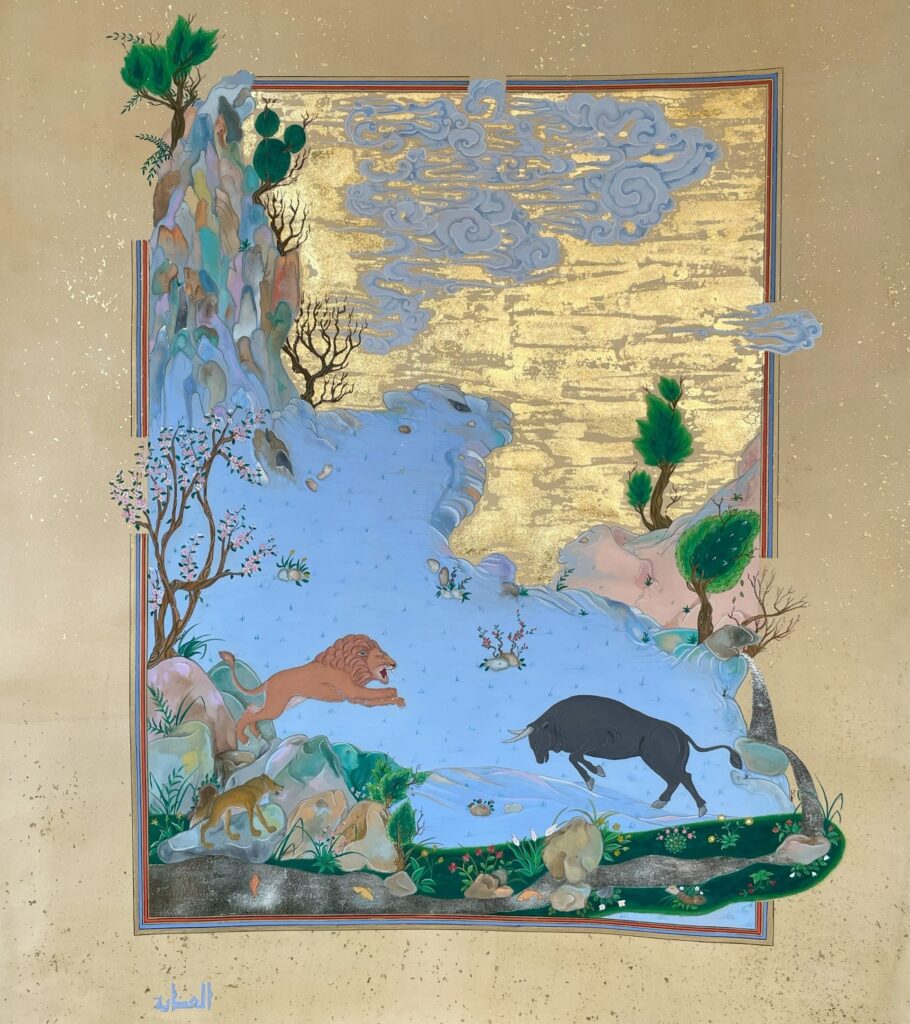

Monréal wasn’t put off. Over the following six months, in most cases accompanied by Sheikh Saoud, he engaged in shuttle diplomacy, continuing a constructive dialogue with Pei. The architect began to soften his stance and even undertook a series of travels in the Muslim world. “It seemed to me that I had to grasp the essence of Islamic architecture,” Pei told the architecture writer Philip Jodidio. He studied landmark Islamic buildings, including the 8th-century Great Mosque of Córdoba and the 16th-century Jama Masjid in the Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri, but failed to identify any defining characteristics that might suggest a design solution. He felt closer to his goal on a trip to Tunisia, where he observed the sun bring to life ancient stone fortresses at Monastir and Sousse.

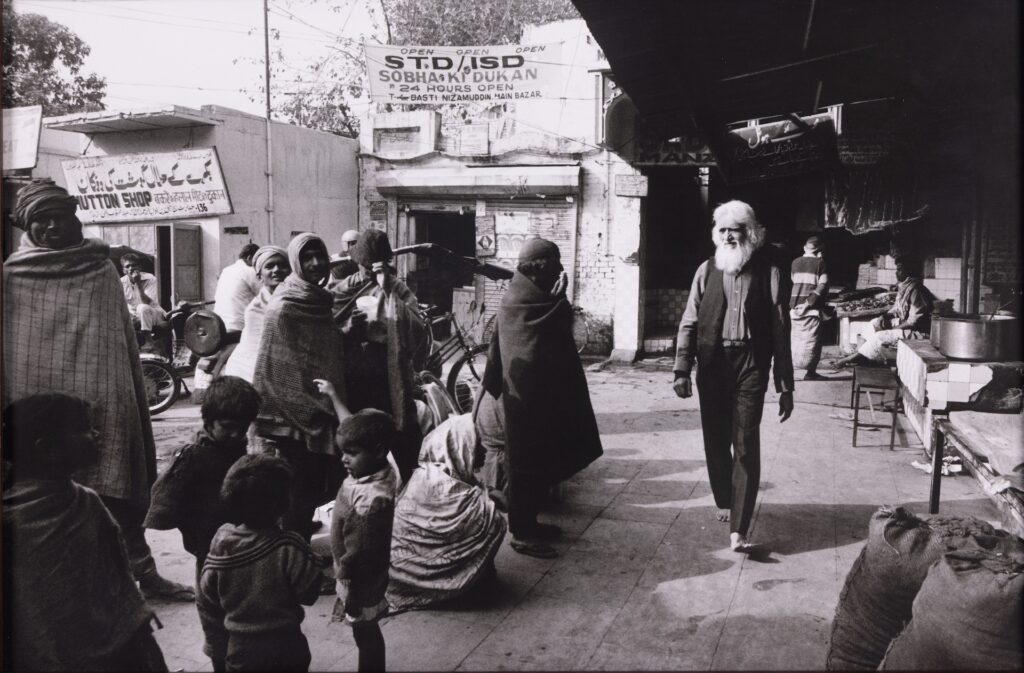

The conversations and travels culminated, at the suggestion of Monréal, in a joint visit to Cairo. The Egyptian capital has possibly the world’s greatest density of historic Islamic architecture, both secular and religious, ranging from the Abbasid era through the glories of the Mamluks to the legacy of more than 350 years of Ottoman Turkish rule. “Cairo is like Florence,” says Monréal. “The concentration of monuments is equivalent.” Pei and Monréal spent an intense three days exploring the old city, which culminated in a visit to the Mosque of Ibn Tulun. It is not Cairo’s oldest, most venerated or imposing mosque, but it was here, while stood in its stone-paved courtyard, that Pei announced: “OK, I think I can do the museum.”

Having made his decision, Pei paid a visit to Doha, where he dined with the Amir and his wife to celebrate the agreement. With a clear idea of what he wanted to do and having spent more time in the Qatari capital, Pei had a request to make: he didn’t want to build on the coastal site earmarked for the museum; instead, he proposed creating a small artificial island in the bay. His reason was that he didn’t want any future development obstructing the movement of sunlight over his building.

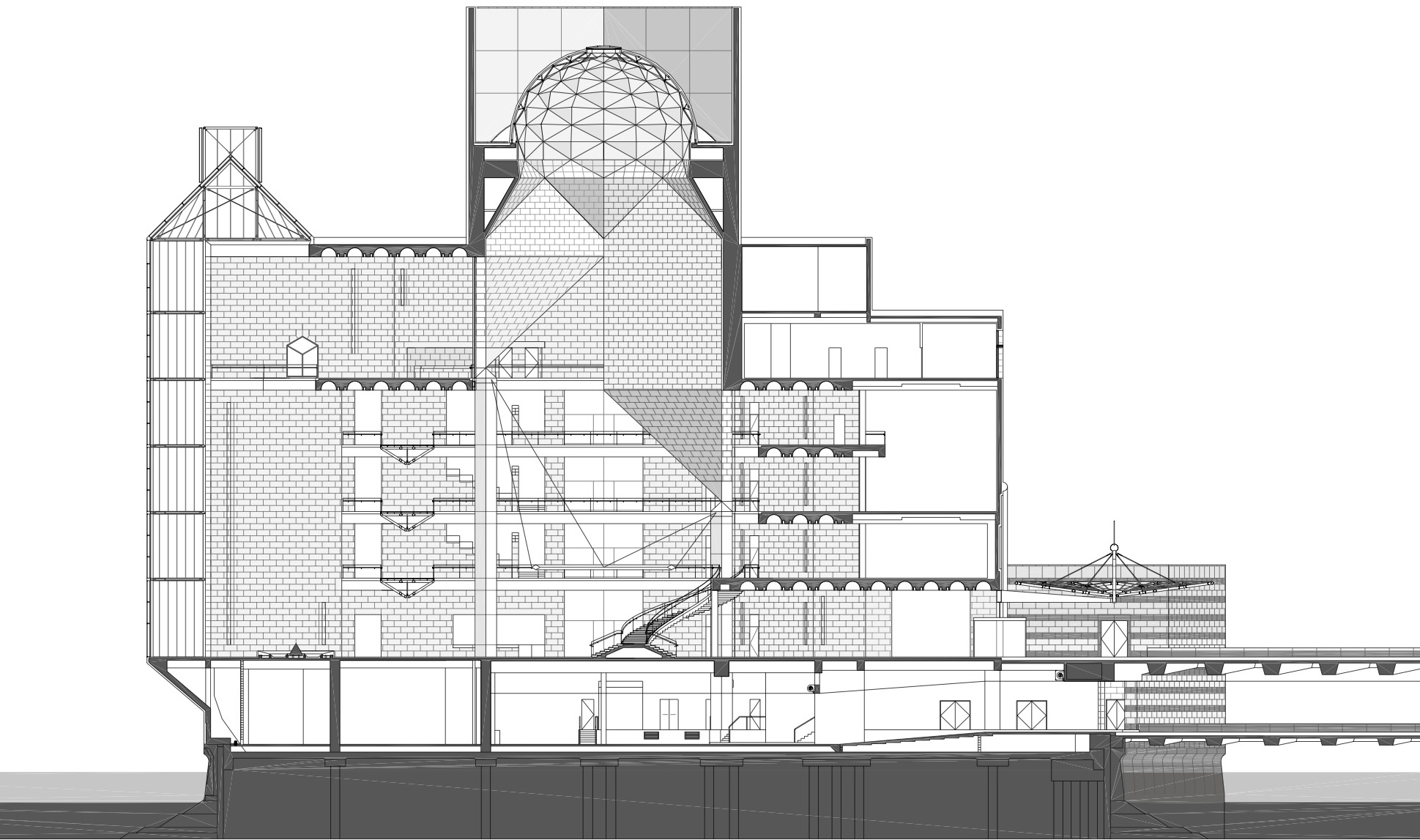

The Mosque of Ibn Tulun has a large open courtyard, roughly square in shape, surrounded on three sides by a single storey of arched arcades. On the fourth side is a similarly low-rise prayer hall. The tallest element is the minaret, which has an unusual external spiral staircase – the only minaret like it in Egypt. At the centre of the courtyard is a small domed building enclosing a fountain for ablutions. It was this structure, with its almost Cubist expression of geometric progression from square base to octagonal transition zone to circular dome, that provided Pei with the inspiration he needed for his museum. It is a geometry that is culturally specific but also universal. It was the way the sun played across its surfaces that provided the key Pei was searching for.

“I remained faithful to the inspiration I had found in the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, derived from its austerity and simplicity,” he told Jodidio. “It was this essence that I attempted to bring forth in the desert sun of Doha. It is the light of the desert that transforms the architecture into a play of light and shadow.”

The upper storeys of MIA’s central tower, which owe a direct debt to the ablutions fountain at the Mosque of Ibn Tulun. Photo: Courtesy of Qatar Museums

“I remained faithful to the inspiration I had found in the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, derived from its austerity and simplicity”

IM Pei

Design of the new museum began in 2000 and MIA was inaugurated in 2008. The influence of the simple ablutions building in Cairo is immediately apparent in Pei’s completed museum. It has a central structure of angular volumes that rise in sequence from square to octagon and then back to a square – the building is topped with a giant cube rotated horizontally at 45 degrees rather than a dome (there is a dome within the cube but only its underside is viewable, high above the soaring atrium). The two main parts of the building are connected by a courtyard with arched arcades.

Reflecting on the project years later, Pei told Jodidio that MIA had been “one of the most difficult jobs I ever undertook”. At the same time, as he celebrated his 100th birthday in 2017, he chose to do so with a cake made in the shape of MIA because, as he explained, the project had been a rejuvenating experience during which he became a student again.

“Obviously, I am not an impartial critic,” says Monréal, speaking in 2025, 17 years after the museum opened, “but I think Pei’s museum fulfils and exceeds the expectations I had for it. It is a monumental building but at the same time has intimacy. It has all the values of monumentalism and none of the inconveniences. And it works very well as a museum on top of all that.”

Further testament to Pei’s vision is that his influence goes beyond the aesthetics of the building and its core functions as a place for display, preservation and education. Thanks to the site he selected, pushed out into the sea – floating like Ahmad Ibn Tulun on his mercury pool – MIA has become a visual beacon in Doha and, together with the National Museum that followed, an iconic symbol of Qatar.

Turkish architect Aslihan Demirtaş was lead project designer on MIA

“I grew up in Ankara and graduated from MIT's Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. On graduating I was interviewed and hired by IM Pei. In the interview he asked: ‘Are you a Muslim?’ and I was thinking: ‘This is the US, you can’t ask questions like that!’ Then he asked: ‘What is Islamic architecture?’ I said I didn’t know because, frankly speaking, it doesn’t exist. Islamic architecture is a very Western-centric notion. If you are in Egypt, then it’s Egyptian architecture, and that doesn’t have anything to do with Andalusian architecture, which doesn’t have anything to do with Iran and the Safavids. They are all different kinds of architecture. It comes from ‘othering’ of an entire culture or religion. Would you use the term Christian architecture?

“There is no such thing as Islamic architecture”

Aslihan Demirtaş

“But I realised he was looking to enter a conversation. He wanted to understand and he was looking at me as a person who knew more than he did about this subject. He was trying to find a point of engagement from which he could nourish or feed his architecture.

“I don’t call it inspiration, because Pei was much more rational than that. He didn’t get inspired, he found a parallel that fitted his own rationality. So, when you look at the structure of the Ibn Tulun Mosque, it’s rational and there’s not much ornamentation. From this, Pei formulated a system and once that system was formulated the design unfolded very quickly.

“There was always a modularity in his design. With the Ibn Tulun Mosque and MIA there is this geometry that keeps rotating. He had to search for this language because when we started the project Doha had just the Sheraton [hotel] as its only large building. Qatar was just at the beginning of reinventing itself. There were no local precedents.”