The Swiss Connection

The world’s most famous art fair is coming to Qatar in 2026 – and the move was a hot topic at Art Basel 2025 in Switzerland

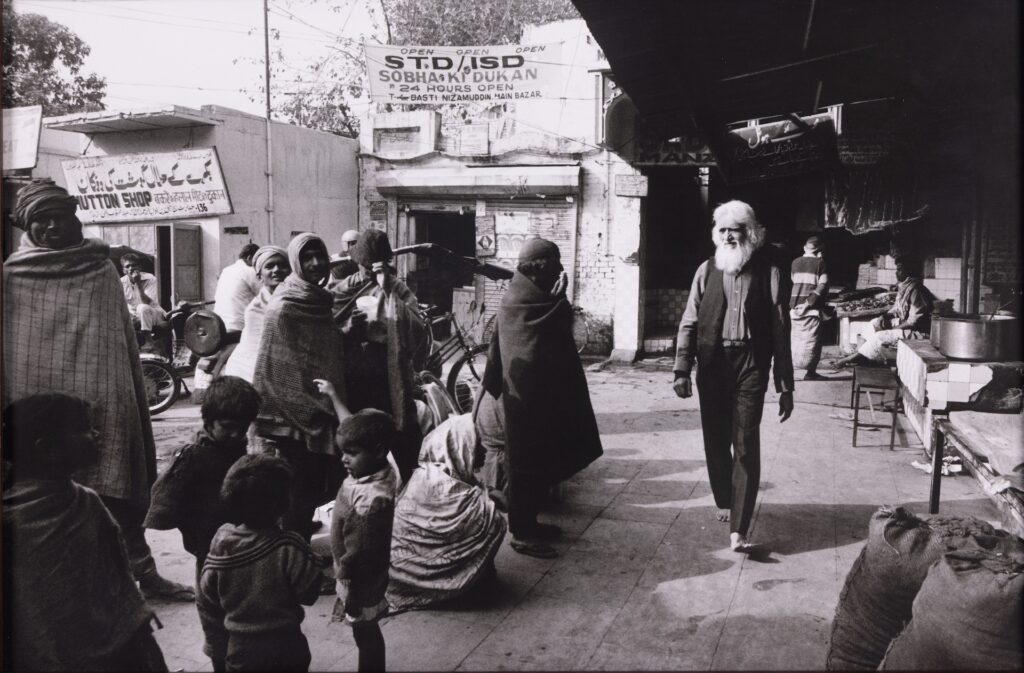

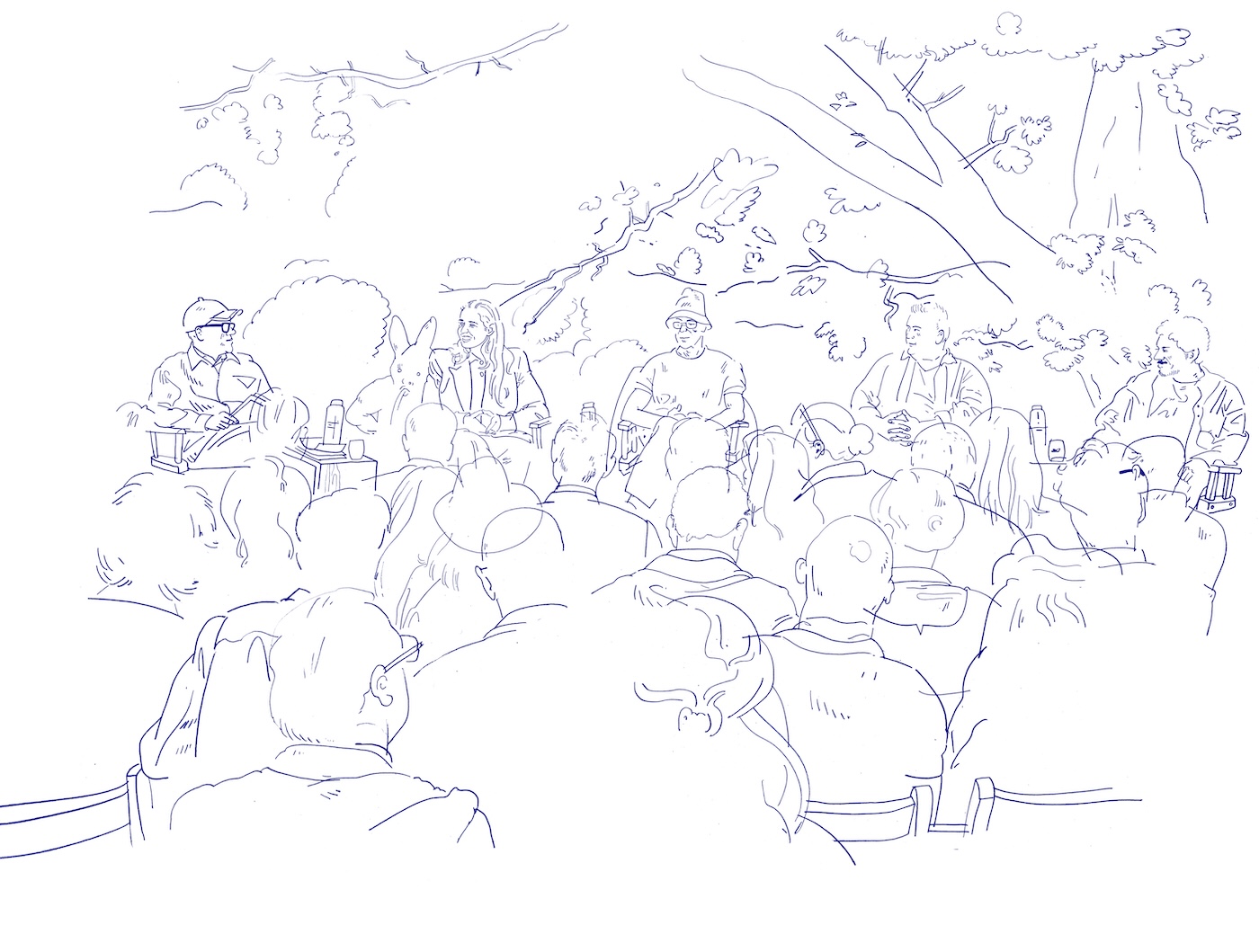

Illustrations Olivier Kugler

As part of Art Basel 2025, a panel discussion titled Beyond the Canon: Art, Architecture and Global Imagination took place at the Fondation Beyeler, in Riehen, near Basel. On stage were Her Excellency Sheikha al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, chairperson of Qatar Museums; curator Hans Ulrich Obrist; architect Jacques Herzog, and the artists Urs Fischer and Wael Shawky. The event was introduced by Noah Horowitz, the chief executive of Art Basel.

These are edited highlights of the conversation.

NOAH HOROWITZ Welcome, everybody. This is an extraordinary turnout. Thank you for joining us here this morning. I’m Noah Horowitz. I’m the CEO of Art Basel and it is a real pleasure to welcome you here today to the Fondation Beyeler to talk about Art Basel Qatar and the Qatari cultural scene.

We announced about a month ago our “fifth pillar” in Qatar. We are thrilled with this development, which will launch in February next year. Further details coming very soon. We’re truly excited about this development, which will add to Paris, Miami, Hong Kong and, of course, our flagship here in Basel. We thought it would be appropriate to host a panel today to underline the connections between Basel and Qatar. So, without further ado, I’m going to hand over to a very dear friend and former colleague, Hans Ulrich Obrist.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST I wanted to begin with a question for Your Excellency. The philosopher Roman Krznaric wrote this amazing book, The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World, and in it he says we need to liberate the world from the predicament of short-termism. We need to engage in long-term visions. I would like you to tell us about the 25-year plan that forms the basis of Qatar’s overarching cultural vision.

Obrist has curated shows in Qatar by American-Lebanese poet and artist Etel Adnan, in 2014, and by the Iraqi-Canadian artist Mahmoud Obaidi, in 2016.

SHEIKHA AL-MAYASSAWe split our 25-year strategy into three parts. The first part, which was the most important for us, is a local authentic voice and identity. So, we opened the Museum of Islamic Art, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art and the National Museum of Qatar. These three institutions are all about who we are, who we were and where we want to go. The second phase, which we’re almost completing now, has been about social development and how to encourage people to utilise arts and culture institutions as knowledge centres and not mere entertainment. We opened the Qatar Olympic and Sports Museum in time for the FIFA World Cup, in 2022, and now we’re working on the Dadu Children’s Museum.

The final chapter is why we’re here today, which is to launch our international and global outreach projects. First, we have the Lusail Museum, which Jacques will be talking about. It is all about the idea of what it means to exist in a post-colonial world and the identity crisis that the region is facing because of that. How do we address conflict using arts and culture as a tool to heal and bring people together?

The second project is the Qatar Auto Museum, for which we have just partnered with the MAUTO Museum in Turin. That’s a museum that Rem Koolhaas is designing, a recycled building, actually. Last but not least is the Art Mill Museum, also a converted building, the restoration of an old flour mill, which will become a museum of modern and contemporary art.

That’s our roadmap, supported by creative hubs such as the Fire Station for artists, the Doha Film Institute for filmmakers, M7 and Liwan Studios for fashion and design. And we’re working on a vocational school to help artists to grow in the field. That’s our long-term strategy and plan. We’ve made sure to be consistent in sticking to it because it’s very easy to get distracted when everybody thinks they know better how you should be doing things.

I think the difference in the model that Qatar has followed in comparison to a lot of other countries is that we have invested in culture with the aim of fostering human development. We want to transform our petrochemical economy into a knowledge-based society.

Sheikha al-Mayassa works in human development, cultural regionalism, environmental stewardship and sustainability, and economic growth using culture as a catalyst for education, dialogue and exchange. She is dedicated to building a creative future for Qatar.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST We’re going to hear more from Jacques about the Lusail Museum, but maybe you can tell us a little bit more about the vision behind it?

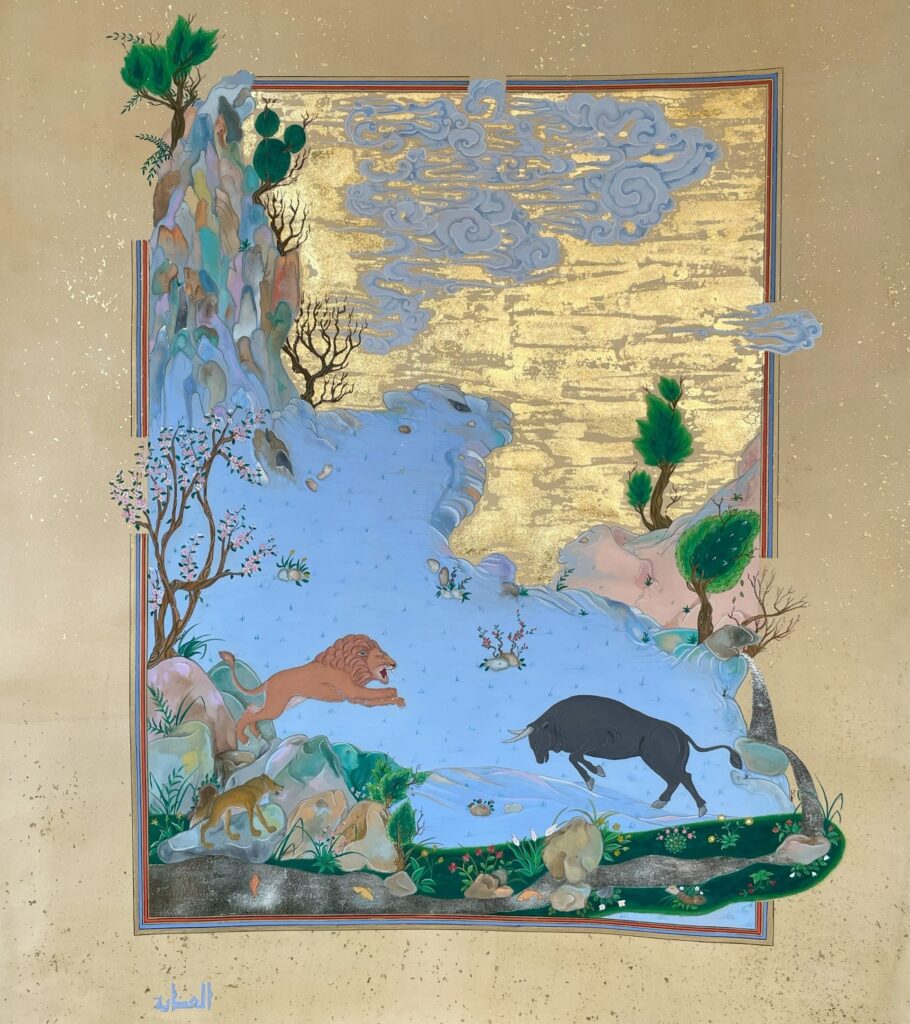

SHEIKHA AL-MAYASSA The Lusail Museum is not just a museum, it’s a whole island. It is being developed based on the collection that we have built over the years focused on Orientalism. These were painters who came from the West and were inspired by and painted the East. This can be a jumping-off point for a lot of dialogue that needs to take place about the many crises we see in our region, about how we can use art and culture to address issues of migration, identity and so forth. It will also house a think tank, which will be in partnership with multiple institutions – we’ve just signed with the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, as well as the Musée Guimet, and with universities such as Brown University, MIT and Georgetown University in Qatar. It’s really about bringing people together to engage in dialogue and project a more optimistic future for those younger generations who are really confused about what’s happening around the world.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST Jacques, could you tell us about Lusail and the museum?

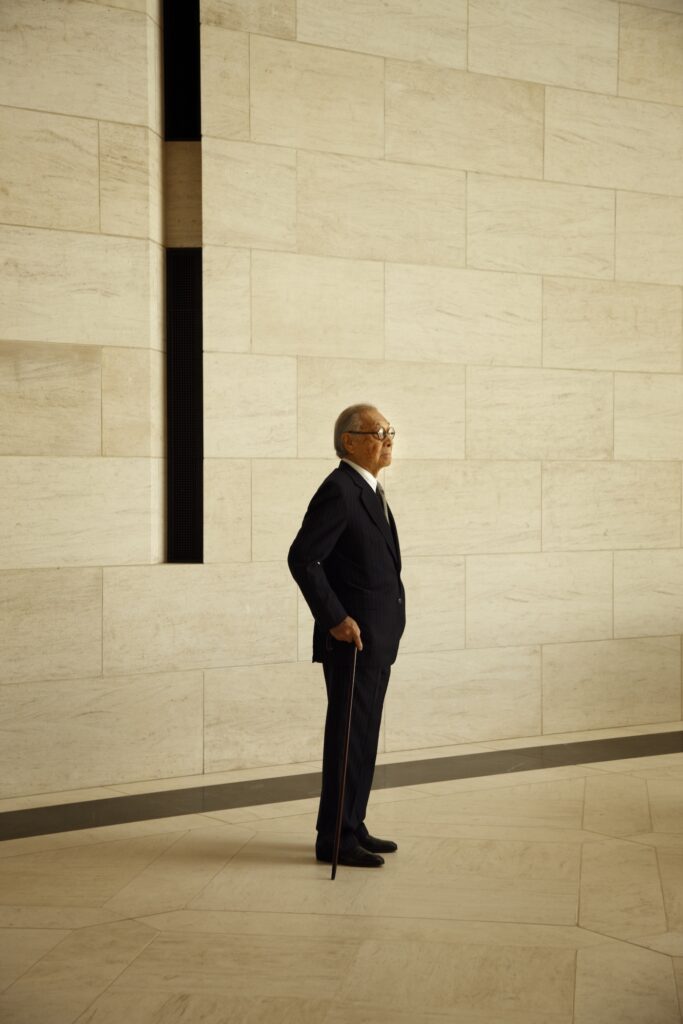

JACQUES HERZOG First of all, I have to say this project is not new on our table. We’ve been working on it for 18 years. When Sheikha al-Mayassa first brought this project to us it was at a totally different site and had a different concept. The world was quite different then. The Lusail Museum was originally called the Orientalist Museum, named because of Qatar’s Orientalist collection, which is maybe the best in the world. Orientalism is something I didn’t know much about when I started this project. Basically, it’s about how the West sees the East and vice versa. Over time, the project has changed from being a museum, where you just present art in the best possible way, to something that is also a platform for political debate and conversations. So this museum has libraries, academic spaces, auditoriums: lots of spaces for people to meet in very close circles – almost like a parliament.

The island on which it is being built is artificial. Much of Qatar’s land is not like in Switzerland – rock that seems to have been there forever – the line between water and land is constantly shifting. Our ambition is to develop new construction technologies where the building itself is formed like the island. Somehow the architecture is about land-making or earth-making. This is not just about making another nice building. Qatar needs to be a model. If you want to realise the transition that Sheikha al-Mayassa just talked about, we have to think: how do you deal with sustainability? These things should not just be hollow words. The museum is a really important milestone in reaching this goal.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST You told me in a conversation we had some years ago that planning something new should always start from already existing features and from the qualities of a specific place. I wanted to ask you in terms of this specific museum what you’re learning from the local context?

JACQUES HERZOG Qatar has a rich history. There are many interesting architectural typologies, such as the house of Sheikh Jassim, the founder of the nation. I think that the whole Muslim world has contributed substantially to the importance of architecture. The Mosque of Cordoba, dating from the 10th century, is one of the most incredible buildings in the world. So whatever we build in Qatar should inscribe itself in the history of architectural contributions.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST Now I’d like to address a question to Urs. I remember some years ago you told me that you were really inspired by Christo and the way he created art that was truly public and brought people together. Can you tell us more about that?

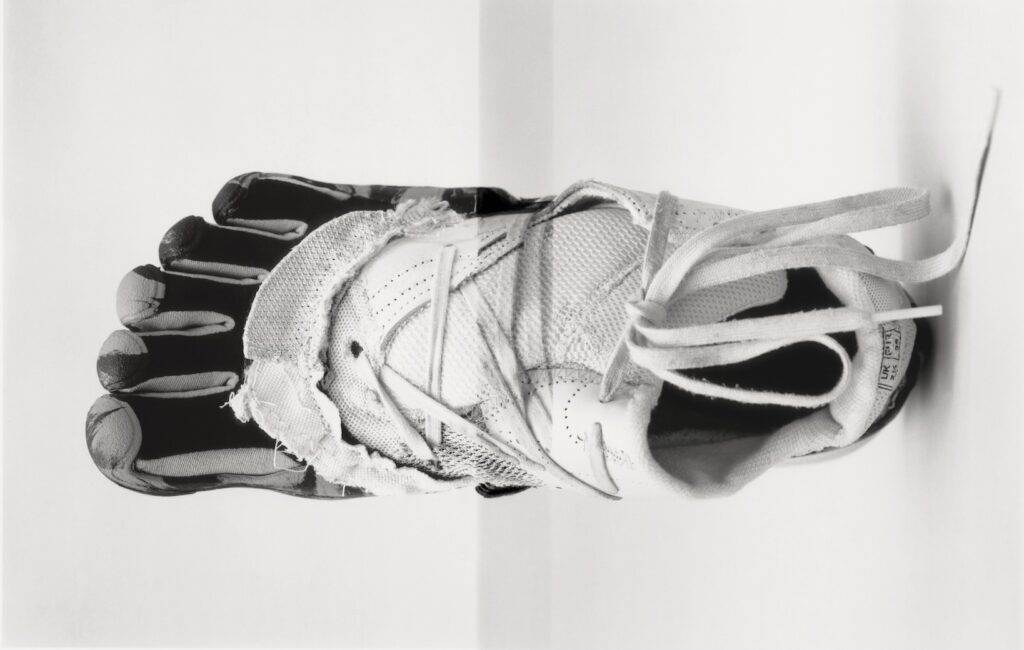

URS FISCHER Well, I was just maybe 12 years old when I saw in a Swiss magazine, Schweizer Illustrierte, pictures of the Florida Keys he had wrapped around with pink fabric [Surrounded Islands, 1980-83]. I just didn’t know what it was. It made no sense. But it was so beautiful – a strange elevation of the landscape through the simple interaction of fabric. I just loved it.

Urs Fischer’s Lamp/Bear is just one of around 20 pieces of public art at Doha airport. They are part of a wider public art programme that has to date installed close to 100 works of art by local, regional and international artists all around Qatar.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST And you yourself have, of course, created such amazing public art. I want to ask you about the Lamp/Bear, which is housed at Hamad International Airport in Qatar. I want to ask how this piece came into being, because it’s a very playful piece that people always gather around. It’s really a place for conversations and chance encounters.

URS FISCHER Well, it didn’t start as a public sculpture intended for such a busy place. That was the Sheikha’s vision, not mine. It came out of a far smaller thing. You know when you have a torch and you shine it up in your face – it can look scary or kind of cute. That’s where the initial idea came from. Then that bear I created started to grow and it became a much bigger object. Then I thought it should be in a city. Eventually it landed up at the airport, where it has a more landmark-y function. When you have the seed of an artwork you don’t really know what it is. Then it goes from this little seed and if it’s successful it can expand. It’s like the Sydney Opera House – it started with somebody being obsessed about some small idea or vision. If the idea is successful, it can become a landmark.

SHEIKHA AL-MAYASSA Can I just tell you an anecdote about Urs’s bear? When I saw it in New York it was outside the Seagram Building. This was around the same time that Hamad International Airport was under construction and its directors had approached us to put art in the airport. I saw this bear and thought that with its weight and height there were not many places you could put it, but the airport would be one. So we installed it and got a lot of criticism. I was criticised. My whole organisation was criticised. Akbar Al Baker, who was then the CEO of the airport, called me and said: “I want this bear removed immediately.” I said: “OK, let me think how to do it, now the airport is open, and let’s talk again in three days.” In less than three days he called me: “You know, this bear is the best thing you did. Thank you so much.” Everybody was stopping by the bear, everybody was taking a selfie. So, you know, it’s always about having a clear vision and strategy, and accepting that at the beginning people may react in a way you don’t anticipate. Now Qatar Airways is an Art Basel partner. I don’t know if I told you that story, Urs, but for a time your bear was going to be kicked out of the airport and now it’s the most popular thing there.

The sculpture was offered for sale by Christie’s New York in May 2011, and prior to the auction was exhibited on Park Avenue.

Visitors to Qatar can buy Lamp/Bear glitter snow globes and plush backpacks at Qatar Museums gift shops.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST Urs, you mentioned Sydney, where you made a very important public work with John Calder, who for many decades invited artists to do things in unexpected places to create encounters in public spaces. Maybe you can tell us a bit more about some other examples of public artworks you’ve made?

URS FISCHER I don’t do that much public art, actually. There are a few projects I’ve made but I prefer to make my work and let it travel somewhere of its own accord and find its place in the world. It’s like it comes from outer space and lands.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST Sheikha al-Mayassa, I wanted to ask you one more question, which is about Switzerland. I know that the country has inspired you and I wanted to ask you to tell us more.

SHEIKHA AL-MAYASSA Well, probably none of you know this but I was born in Switzerland. In Geneva. I’ve been coming to Basel from the very beginning. I love the art fair. I think the ecosystem here is quite unique and I’m always happy to be back. I love the museums, the Beyeler, Schaulager, Kunsthaus, Kunsthalle. And Zurich is an hour away and it has great museums and galleries, too. Obviously my relationship with Basel is also embedded with Herzog & de Meuron’s Lusail project, and I come here a few times a year to discuss progress. When myself and my siblings were growing up my parents always said Switzerland was a benchmark in terms of the quality of education and lifestyle. That became integral to my country’s Qatar National Vision 2030 plan – an investment in human development with a quality of life that invites everybody to integrate into a community. I’m always happy to be in Switzerland and I really look forward to 2029, when we have a year-long programme of events between Qatar and Switzerland as part of our ongoing Years of Culture programme. I’m hoping parts of Jacques’ island will be ready by then.

Sheikha al-Mayassa’s parents are Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, ruling Amir of Qatar from 1995 until 2013, and Sheikha Moza bint Nasser Al Missned. Sheikha al-Mayassa’s brother is the current Amir of Qatar, His Highness Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.