As Qatar’s Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art celebrates its 15th anniversary, its director, Zeina Arida, tells us how it has transformed perceptions of art from the region

Words Aimee Dawson

Mathaf director Zeina Arida in front of the museum in August 2025. Photo: Joseph Ouechen

The first was the museum’s retrospective earlier this year of the artist Wafa Al Hamad (1964-2012), which introduced the pioneering female Qatari artist to a wider public in her first ever institutional exhibition, cementing her role in the region’s art history. The second is the rise to international artworld fame of Qatari-American artist and writer Sophia Al Maria, which was greatly informed by a period working at Mathaf. “The job was really special. It was essentially archiving a library that had been collected by Sheikh Hassan [the museum’s founder] over the years,” said Al Maria in an episode of Sheikha al-Mayassa Al Thani’s The Power of Culture podcast. “I really credit that with being a huge part of my art education. Without it, my education would have been incomplete.”

These two examples capture the essence of Mathaf’s mission. “Our aim is to collect, preserve, study and diffuse the works of artists from the Arab world, mostly from the modern period, but also the contemporary,” says Beirut-born Zeina Arida, the museum’s director since 2021.

El Anatsui’s Black Block, 2010, a wall hanging made from bottle caps and copper wire, exhibited at Mathaf in 2019. Photos: Courtesy of Qatar Museums

Mathaf, which means “museum” in Arabic, was founded with the aim of challenging the traditional Western-centric narrative of art history that marginalises non-Western art and artists. With more than 9,000 artworks in its collection and an approximately 5,500-square-metre space in Doha’s Education City, it is supremely well equipped for the task. One of its inaugural exhibitions was Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, curated by Nada Shabout, Wassan Al Khudhairi and Deena Chalabi, which presented more than 200 works from Mathaf’s collection organised in 10 themed categories. “Sajjil was ideologically constructed towards decolonising the canon of art history, moving away from the idea that European and non-European art are not equal,” says Shabout, a scholar specialising in modern Arab art. “It was an exhibition that initiated a lot of research.”

“I really credit [Mathaf] with being a huge part of my art education. Without it, my education would have been incomplete”

Sophia Al Maria

Mathaf, which means “museum” in Arabic, was founded with the aim of challenging the traditional Western-centric narrative of art history that marginalises non-Western art and artists. With more than 9,000 artworks in its collection and an approximately 5,500-square-metre space in Doha’s Education City, it is supremely well equipped for the task. One of its inaugural exhibitions was Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, curated by Nada Shabout, Wassan Al Khudhairi and Deena Chalabi, which presented more than 200 works from Mathaf’s collection organised in 10 themed categories. “Sajjil was ideologically constructed towards decolonising the canon of art history, moving away from the idea that European and non-European art are not equal,” says Shabout, a scholar specialising in modern Arab art. “It was an exhibition that initiated a lot of research.”

The story of Mathaf’s collection dates back to the 1990s, when Sheikh Hassan bin Mohamed bin Ali Al Thani, a member of the Qatari royal family who is also an artist, began collecting art and supporting artists from the region. With the Gulf War in progress in nearby Iraq, Sheikh Hassan decided to initiate a residency programme for artists from that country, welcoming some of the most celebrated figures from the contemporary Arab art world, including Ismail Azzam, Dia Azzawi and Ismail Fattah. Over time, the initiative expanded to embrace artists from other Arab countries. At the same time, under the tutelage of Qatari artist Yousef Ahmad, Sheikh Hassan began acquiring works by artists from the region. The nascent collection was initially displayed in two private villas.

“Sheikh Hassan was buying modern Arab art when few other people were looking at it,” says Arida. “So Mathaf has masterpieces that, even with a limitless budget, you couldn’t find on the market today.” Another reason the collection is special is its depth. “We have whole bodies of work, maybe around 15 to 20, or in some cases hundreds, of meaningful works by important artists,” Arida adds. Cases in point include the Egyptian artist Inji Efflatoun (1924-89), whose depictions of social injustices landed her in prison, and MF Husain (1915-2011), one of the greatest modern painters of India.

Mona Hatoum’s Mathaf installation Suspended, 2011, was a room filled with red and black swings, like a floating archipelago. Courtesy of Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art. © 2025 Mona Hatoum

While there are other significant Modern Arab art collections in the world – such as those of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation in Beirut and the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah – Mathaf is the only major non-private collection. In 2004 Sheikh Hassan gave the entire collection to the Qatar Foundation and, in 2009, it was transferred to Qatar Museums. As well as being the founder of Mathaf, Sheikh Hassan now acts as vice-chairperson of Qatar Museums and advisor for cultural affairs at the Qatar Foundation. Even with such a vast collection, the museum continues to acquire works, says Arida.

“Mathaf has masterpieces that, even with a limitless budget, you couldn’t find on the market today”

Zeina Arida

While there are other significant Modern Arab art collections in the world – such as those of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation in Beirut and the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah – Mathaf is the only major non-private collection. In 2004 Sheikh Hassan gave the entire collection to the Qatar Foundation and, in 2009, it was transferred to Qatar Museums. As well as being the founder of Mathaf, Sheikh Hassan now acts as vice-chairperson of Qatar Museums and advisor for cultural affairs at the Qatar Foundation. Even with such a vast collection, the museum continues to acquire works, says Arida.

Mathaf’s location, in a former school building in Education City, close to no less than eight university campuses, greatly helps the museum in its scholarly ambitions. Its main educational initiative is the Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Arab World, which publishes peer-reviewed artist biographies, interviews and essays written by scholars in English and Arabic – an essential resource in a region where information about many artists is not publicly available, standardised or translated. “It gives curators, scholars and museums much-needed access. The more information we can build about these artists, the more visibility we can give them at an international level,” says Arida. Nada Shabout, who worked to develop the encyclopedia, says it has already had an impact: “Some artists have become household names because of Mathaf.”

Yan Pei-Ming’s portraits of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani and Sheikha Moza bint Nasser Al Missned. Courtesy of Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art

This year the museum is developing an enhanced online platform that will merge the encyclopedia with the Mathaf website, increasing its accessibility. Arida hopes this will aid collaboration and co-production on more major exhibitions in the future. “I feel that today we are entering a new phase, which is the internationalisation of artists from our region. There is a much stronger interest from around the world and we are getting ever more requests for international loans.” In 2024 Mathaf loaned important works to the Venice Biennale and in 2025 more than 15 of its paintings were included in All Manner of Experiments: Legacies of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, an exhibition at Bard College’s Hessel Museum of Art in New York. A version of the show will travel to Mathaf in 2026.

In the meantime Mathaf is staging two anniversary exhibitions. The first is Resolution: Celebrating 15 Years of Mathaf. “We believe it’s very important, particularly in the Arab world, to preserve and highlight institutional history,” says Arida. “The idea behind this exhibition, but also the work we are doing at Mathaf in general, is to show there is a very long-term commitment to culture here, and that started way before the museum opened its doors.”

“Some artists have become household names because of Mathaf”

Nada Shabout

The show is in four sections: the first looks at the collection prior to the opening of Mathaf and includes photographs, artists’ letters and interviews relating to Sheikh Hassan and Yousef Ahmad; the second explores art of the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s and its portrayal of Arab identity in the context of postcolonialism; a section about education looks at the many modern Arab artists who taught alongside their own artistic practice, and the final part presents an overview of the more than 60 exhibitions Mathaf has held to date. Running alongside Resolutions is a group show of 15 contemporary artists titled We Refuse_d, conceived by Turkish curator Vasif Kortun and Swiss-Egyptian art historian Nadia Radwan. “What links all the artists is that they have all had to deal with censorship or cancellation in the past two years because of the country they are from or for voicing their support for Palestine,” says Arida.

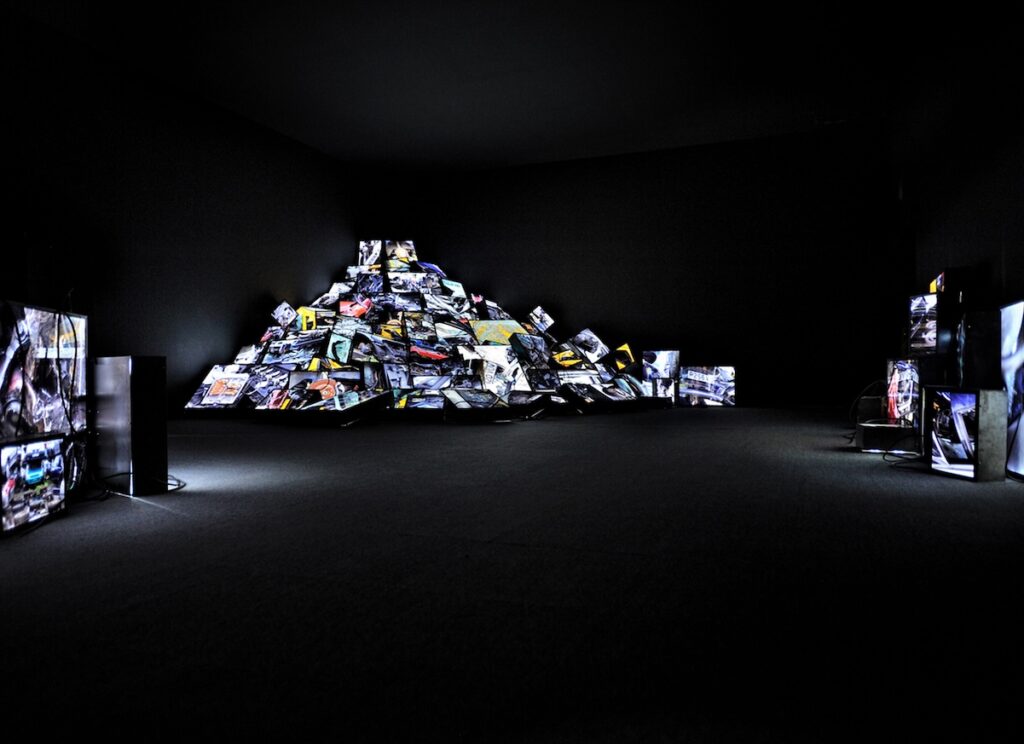

Adel Abdessemed’s hellish vision of toil, Shams (Sun), filled a whole room at Mathaf for the duration of his 2013 exhibition L’âge d’or. Photos: Courtesy of Qatar Museums

The show was inspired by the last-minute cancellation of 88-year-old Palestinian-American artist Samia Halaby’s exhibition at Indiana University in the US, over her social media posts expressing support for Palestinian causes and outrage at the violence being perpetrated in Gaza. “It’s really an exhibition that reaffirms the role of Mathaf as a platform and a safe place for artists to produce their work and share it with an audience,” Arida adds.

Looking further ahead, there are ambitious plans in place to expand Mathaf’s programmes and campus by 2027, creating residency spaces for artists working in specific disciplines, including ceramics, glass, textiles and digital technologies. “If you are a ceramicist in our region and you want to make a large-scale piece you have to travel to Europe or the US. Our new residency spaces will support artists and give them access to facilities that don’t yet exist in the Arab world,” says Arida. It’s a development inspired by the early residencies that Sheikh Hassan facilitated, bringing Mathaf’s story full circle.

“Mathaf was the first major museum to support artistic production and the study and preservation of art in the Arab world. Fifteen years on, our plans will reaffirm the need for such an institution,” says Arida. “The Arab world has evolved a lot in recent years but conflicts have also spread. We believe the role of Mathaf as a platform to support and gather artists from across the region is more relevant than ever.”

Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, 2010

The public was welcomed to the new museum with a show of more than 200 works from Mathaf’s collection, representing more than 120 artists. The curators chose ten themed categories that served to highlight decisive moments in artistic thought as it evolved in the region, emphasising common concerns.

Told/Untold/Retold, 2010

Conceived by guest curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, this inaugural show presented commissions from 23 artists with roots in the Arab world to emphasise Mathaf’s potential to make Doha a site of artistic production. It included Wafaa Bilal’s interactive media installation 3rdi, 2010, in which the artist had a thumbnail camera surgically attached to the back of his head.

Adel Abdessemed: L’âge d’or, 2013

Best known for his towering statue of French footballer Zinedine Zidane headbutting the Italian player Marco Materazzi, work in the French-Algerian artist’s solo show was similarly provocative. It included a monumental terracotta wall relief, Shams, 2013, that was created in situ using 40 tonnes of clay and depicted workers labouring under observation by armed soldiers.

Tea with Nefertiti, 2013

A second Bardaouil and Fellrath show for Mathaf offered a critique of museology and the way art can become a tool in the construction of a narrative through which an image of another culture can be framed. The exhibition featured work by more than 40 artists. Following its debut in Doha, the show travelled to the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, the Institut Valencia d’Art Modern in Spain and the Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst in Munich.

Mona Hatoum: Turbulence, 2014

This was the largest exhibition to date in the Arab world by the British-Palestinian artist. It brought together more than 70 works – ranging from large-scale room installations to smaller works on paper and documentations of early performances – to highlight the diversity of Hatoum’s artistic endeavours.

Etel Adnan in All Her Dimensions, 2014

A retrospective of the Beirut-born artist, poet, novelist, playwright and essayist curated by Swiss critic, art historian and Serpentine Galleries director Hans Ulrich Obrist. It included examples of her paintings, drawings, writing, films and tapestries.

Dia Azzawi: I Am the Cry, Who Will Give Voice to Me?, 2016

A vast retrospective of the pioneering Iraqi artist and sometime Doha resident that spread over two venues. It brought together more than 350 works, including pieces informed by the artist’s response to the 2003 American-led invasion of Iraq, notably a 150-metre-long canvas railing against the destruction of cultural institutions that occurred in the wake of the occupation.

El Anatsui: Triumphant Scale, 2019

Four years after receiving the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale, this was the Ghanaian artist’s first major show in the Middle East. It included works in every media used by Anatsui in his 50-year career, including wood sculptures, wall reliefs, ceramics, drawings and prints.

Kader Attia: On Silence, 2021

Two major new works were commissioned for this show, notably On Silence, 2021, an installation of limb prostheses worn by people who have been injured in conflict zones. The show also included some of Attia’s early works, including the installation Ghost, 2007, which features a group of Muslim women in prayer made from aluminium foil.

Sophia Al Maria: INVISIBLE LABORS daydream therapy, 2022

Winner of the Frieze London Artist Award 2025, Qatari-American artist Al Maria once worked as an archivist at Mathaf. Her triumphant headlining return to the museum saw its exhibition spaces transformed into a site for a show that bridged the present, past and future of Doha.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

These cookies are needed for adding comments on this website.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: policies.google.com (opens in a new window)