A place to live,

not to leave

A new Qatar edition of a 2020 Guggenheim New York exhibition continues to probe the past, present and future of the countryside

Words Debika Ray

A place to live, not to leave

A new Qatar edition of a 2020 Guggenheim New York exhibition continues to probe the past, present and future of the countryside

Words Debika Ray

"Humankind does not have to live in cities. For our survival as a species we need to be able to live in the countryside as well,” says Samir Bantal, director of AMO, the research arm of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), the practice co-founded by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas.

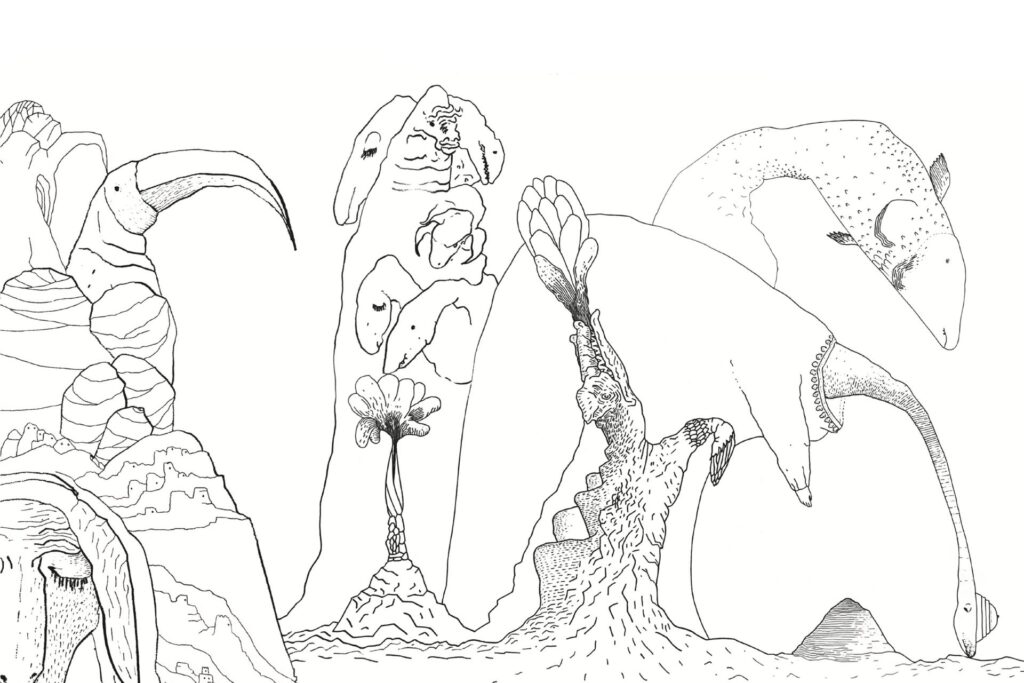

In October 2025 the studio opened an exhibition in Qatar called Countryside: A Place to Live, Not to Leave, which invites viewers to consider the 98% of the world’s surface not occupied by cities. The message is clear: instead of people leaving the countryside, maybe we should return to it and preserve it, because we’re now seeing the limitations of urbanisation.

The exhibition is a new iteration of a show, Countryside, The Future, which took place at the Guggenheim in New York in 2020. Qatar Museums sponsored the show and the intention was always to bring it to Doha one day. With Bantal and Koolhaas as masterminds, Countryside, The Future occupied the entirety of the New York museum’s famous rotunda, as well as spilling out onto the street in the form of an urban greenhouse full of growing tomatoes outside the building’s entrance. Their theorising was triggered by a historic milestone: the moment in 2007 when the world’s urban population surpassed its rural one.

For the AMO/OMA team this raised existential questions, such as whether it is inevitable that we will eventually all live in cities, and whether that is a desirable outcome. It also prompted them to reflect on how little they knew about the areas humans were leaving behind. The result was less an attempt to unequivocally define the countryside than to show “proof of radical change” through a series of examples – drawn from various contexts in Europe, the Americas, Africa, East Asia and Australia.

Case studies included vast industrialised farms – technologically advanced facilities in which workers use jargon to rival Silicon Valley – and enormous data centres where much of the work is done by robots. “These advancements came at a cost, though – uniformisation and a decrease in diversity in farming, for example,” says Bantal. What emerged was that the nostalgic image we have of the countryside as old-fashioned and static was wrong. “The countryside in these places is incredibly dynamic, agile and maybe more progressive than any city. It’s able to embrace technology more easily, which is changing it at an incredible pace.”

This conclusion was thrown into stark relief by the Covid-19 pandemic, which hit the world a month after the Guggenheim show opened. This global catastrophe disrupted urban centres, while country life more or less continued – so-called “smart” urban centres were extraordinarily vulnerable. “What is ‘smartness’ if it falls apart because of a virus?” Bantal asks.

Five years later, with the environmental crisis accelerating, the question of how we inhabit the planet is, if anything, more urgent – with implications for everything from food security to climate adaptation. In this context the restaging of the exhibition in Doha feels timely. There is a new emphasis, though: while research for the original show will be exhibited, the new iteration is less a survey of interesting developments than a call to action to re-embrace the rural in a world sleepwalking into urban oblivion. “We wanted to show that we have another alternative,” says Bantal. In keeping with its location in a 1950s former school building, it will engage its audiences in actively imagining a rural future.

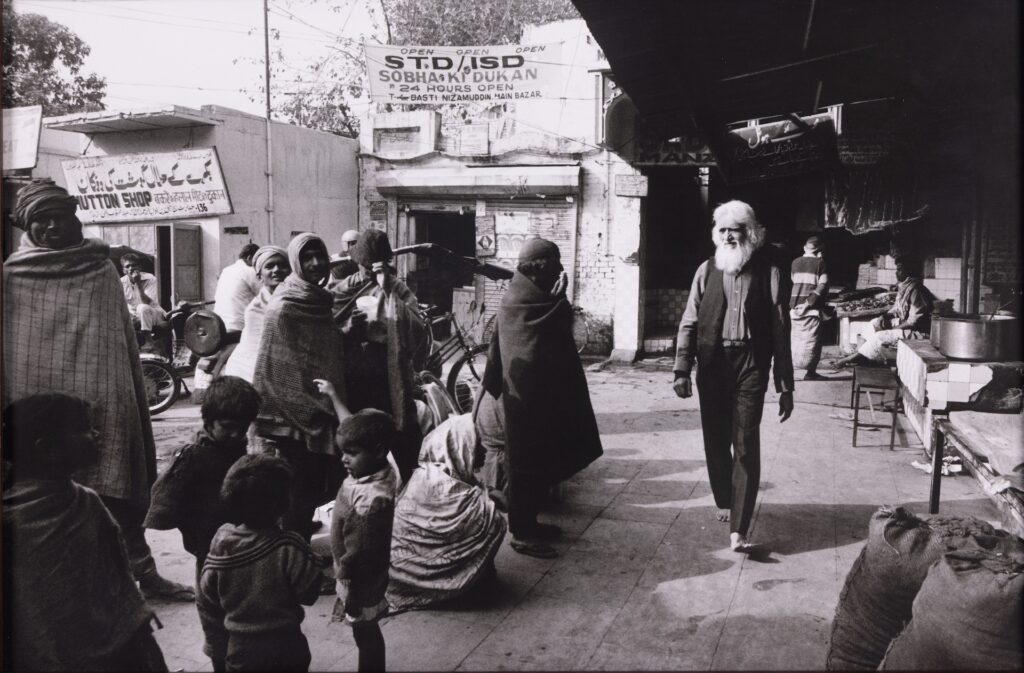

The new show also shifts the geographical focus – a recognition of its location in Qatar and the geopolitical shifts over the past few decades, as the populations of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, already home to 80% of the world’s people, grow in size and power. “Qatar has a strong connection to the East – to India, Pakistan and China – through ancient connections via the silk routes and today through labour,” says Bantal. “There are also connections to Africa, somewhere crucial for its food security.” While the original exhibition’s scope was expansive, it was not comprehensive and, perhaps because of its focus on rapid technological change, it didn’t adequately focus on this large part of the world that Bantal refers to as a “forgotten part of a forgotten realm”.

Expanding outwards, the curators identified an arc running from Africa, through the Middle East and Central Asia, to Mongolia and China. “This arc encompasses 35 countries and two of the most important ocean passages in the world – the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea,” says Bantal. “The region was the birthplace of modern man, and contains some of our oldest civilisations. The connections between its villages and towns were what made European cities thrive.”

And yet this region has been relatively untouched by industrialisation. “It’s the largest span of countryside in the world, not full of the megacities we see in China, India or Europe, partly because much of it is landlocked and has a mountainous topography.” Culturally, he says, there’s a deeper understanding of traditional ways of living and many nomadic communities. While this fragmentation has challenges, it also makes it well equipped to face some of today’s global problems. “It’s one of the least polluting areas of the world,” adds Bantal. “It experienced fewer Covid-19 deaths partly because of its remoteness, but also because of the existing networks of villages and rural health workers in some places.”

A still from Countryside, The Future, 2020. Courtesy of OMA/AMO

“In the past decades, I have noticed that, while much of our energies and intelligence have been focused on the urban areas of the world, the countryside has changed almost beyond recognition”

Rem Koolhaas

The cities in this region have similar problems to elsewhere – polluted, congested and too expensive for young people to buy homes. In response, Bantal says, some governments and people are exploring a different vision of progress to the 20th-century norm of ceaseless urban development. “The focus used to be on hyper-concentrated cities of 20 million people, but now they are asking: ‘Do we really need that?’”

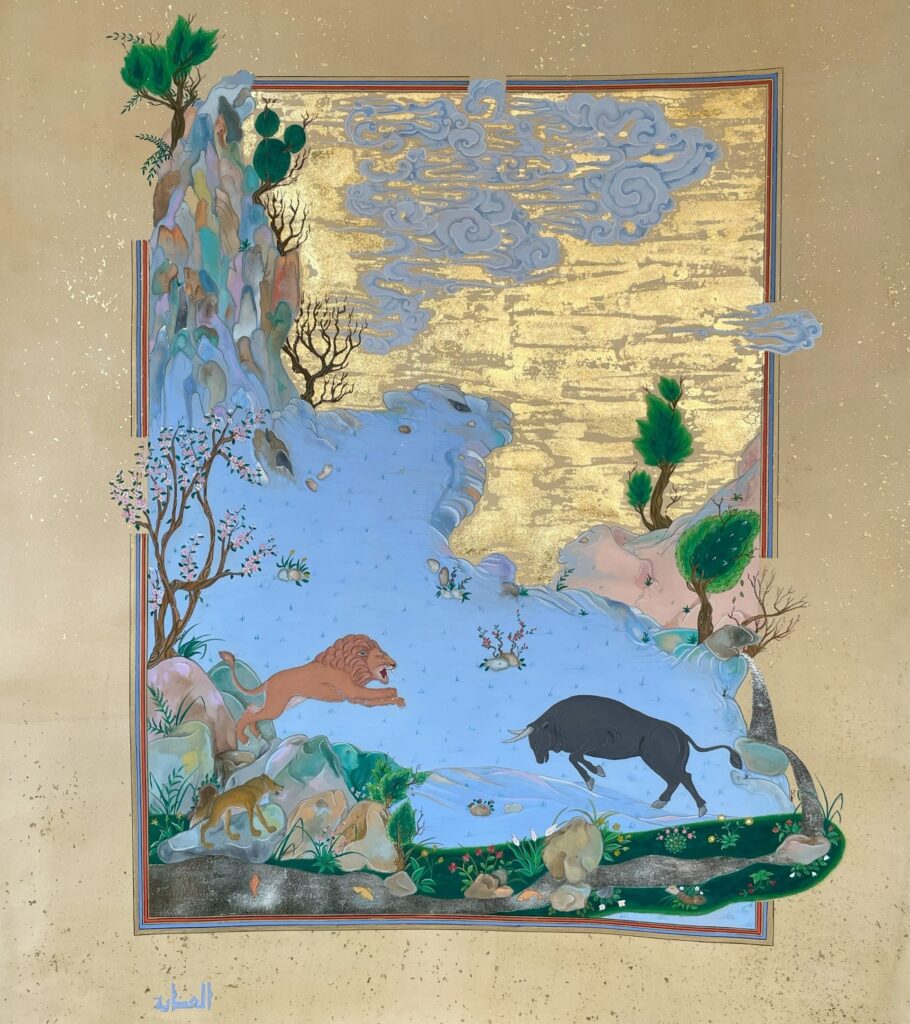

At the heart of this shift, he believes, is a cultural change. “Younger generations are rethinking the relationship between tradition and future, and considering a more networked countryside where they can be close to their roots, while profiting from everything a city can offer.” In practice, this means including more diverse ways of living than those depicted in the 2020 exhibition – including “hybrids of futuristic, tech-driven farming combined with traditional forms”. Examples include people in Kenyan villages who are using mobile phone money transfer services to trade without going to the city; and digitised versions of traditional money raising systems, such as the sanduks historically used by women in South Sudan to pool funds and make loans to those in need.

Where might we go from here? Cities were born out of industrialisation, which is why we tend to live near working environments. In the digital age, though, humans may still want to live together and pool resources. “Are there different formats for that?” Bantal asks. Life in the countryside will require intentional design if we are to avoid the same problems that beset cities, as well as something of a rebrand to make it more appealing for the millions who prefer, or have to endure, metropolitan life. Bantal is starting to see this in the Gulf states: in Qatar and elsewhere the idea of beachfront luxury is giving way to something more authentic to the region. “Now the ‘cool’ place to be is the desert, in more sustainable, low-rise communities that resemble how people used to live there.”

Is it time to abandon cities? And if an exodus of city dwellers transforms the rural environment beyond recognition, what then defines it? For all the exhibition’s advocacy for the countryside, Bantal acknowledges that these divisions are an oversimplification. The arc they looked at, for example, may be largely rural, but it’s also very populated – in other words, in vast parts of the world people are living between the two extremes. “We tend to think in binaries, but it doesn’t need to be an either/or. We’re on the brink of redefining what the city and the countryside mean.”

Prepping for the future

One of two sites at which Countryside: A Place to Live, Not to Leave is being shown is the Qatar Preparatory School (QPS), one of the oldest educational establishments in the country. The school bell rang for the last time many years ago and the building is currently in the process of being converted into a vocational college. When it opens, QPS will train future generations in traditional skills such as carpentry, metalworking and pottery, but also in 21st-century design technologies and techniques, such as 3D printing, robotics, synthetic biology, and digital and parametric design. The school conversion is being undertaken by the French industrial architect and designer Philippe Starck.

OMA and Qatar

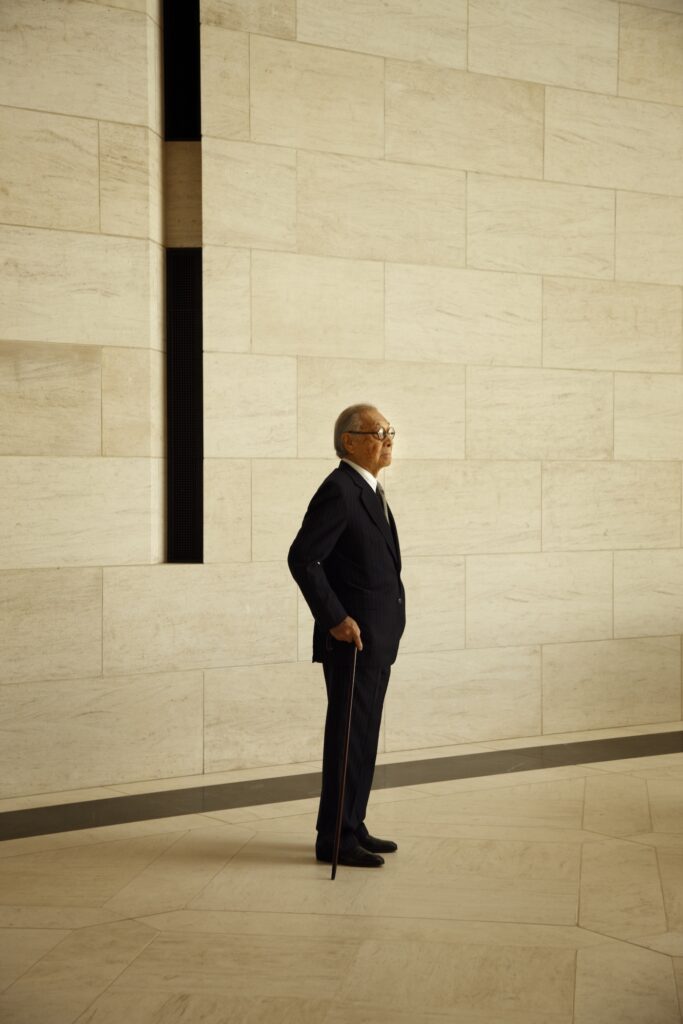

Rem Koolhaas first visited Qatar after receiving a letter from its government expressing interest in engaging a group of architects to build there. This led to commissions for the practice he co-founded, OMA, to design the Qatar National Library and the headquarters of the Qatar Foundation, an organisation focused on education, science and community development.

OMA’s relationship with Qatar has since deepened: the studio is now working on the Qatar Auto Museum, which will explore the past, present and future of the automobile, and collaborating on the Qatar Blueprint, which aims to better connect the urban landscape with its natural habitats and the people who live in them. “At a small scale you can, paradoxically, have larger and more coherent ambitions than you can for a huge country that is simply beyond the reach of a single ambition,” said Koolhaas in a recent podcast interview with Sheikha al-Mayassa. The Blueprint represents a step beyond examining and advocating for the countryside, towards attempting real-world transformation.